Posts Tagged ‘progressive fatalism’

Americans Sound Confused About Equality if You Ask the Wrong Question

According to Drew Desilver at the Pew Research Center, most Americans (65%) agree that the gap between the rich and everyone else is growing, which is true. “But ask people why the gap has grown, and their answers are all over the place.”

Among people who said the gap between the rich and everyone else has grown, we asked an “open-ended question” — what, in their own words, the main reason was. About a fifth (20%) said tax loopholes (or, more generally, tax laws skewed to favor the rich) were the main reason. Ten percent pinned the blame on Congress or government policies more broadly; about as many (9%) cited the lackluster job market, while 6% named corporations or business executives.

But well over half of the people who saw a widening gap cited a host of other reasons, among them (in no particular order): Obama and Democrats, Bush and Republicans, the education system, the capitalist system, the stock market, banks, lobbyists, the strong/weak work ethic of the rich/poor, too much public assistance, not enough public assistance, over-regulation, under-regulation, the rich having more power and opportunity, the rich not spending enough, and simply “a lot of greedy people out there.”

This is presented as a combination of public confusion and disagreement. Read the rest of this entry »

Public Support for Abortion Rights and the Perils of “Support”

Jodi Jacobson, at RH Reality Check, talks about the disconnect between the public and politicians on abortion, which touches on something I’ve been emphasizing here.

Consistent rejection by actual voters of attempts to give the state control over women’s bodies tells us three things. One, polls that attempt to divide people into neat boxes such as “pro-choice” and “pro-life” or to measure support for hypothetical restrictions on abortion in generic terms do not reflect how people really feel about safe abortion care. In fact, when asked specifically about who should make decisions on how and when to bear children and under what circumstances to terminate a pregnancy, voters make clear they do not want to interfere in the deeply personal decisions they believe belong between a woman, her partner and family, and her medical advisers, even in cases of later abortion. In short, voters do not want legislators playing god or doctor.

Blaming Consumers is a Cop Out

[Update: On Orhtheory, Jerry Davis object to my comment (which was the first draft of this post) for claiming that he is calling to blame the consumer.]

[Update 2: Davis also makes his objections in this comments to this post. My response is here]

[Update 3: Jim Naureckas has a good post on this topic: You’re to Blame for Factory Deaths. Well, You and Walmart]

[Update 4: You can take the National Consumers’ League 10 cent pledge here.]

Speaking of the awful Bangladesh factory disaster that killed at least a thousand people, Brayden King at Orgtheory quotes Jerry Davis in the New York Times who blames consumers for working conditions in the Third World. In essence, consumer demand for cheap products are what forces wages down and makes working conditions so dangerous, so the blame lies with those consumers.

I see a few problems with this. First, if the all-powerful consumer was driving this, we wouldn’t see businesses making high profits, because that too raises costs. This is not the case. Second, even with expensive goods, where consumers are willing and even eager to pay high prices, we see similar working conditions (think Apple products).

White Working Class, Progressive Fatalism and the Perils of Polling

In the Democratic Strategist, Andrew Levinson (pdf) tries to bring some reality to discussion of the white working class, which is generally stereotypes as monolithic and regressive. This is more evidence against the idea that ‘American is a conservative nation’ as a catch-all explanation for politics, and the progressive fatalism that view leads to.

The majority of white working class Americans are simply not firm, deeply committed conservatives. Those who express “strong” support for conservative propositions represent slightly less than 40% of the total. The critical swing group within white working class America is composed of the ambivalent or open-minded.

This is an extremely surprising result since virtually all political commentary about the white working class today is based on the assumption that these voters are generally quite deeply conservative and that conservatives very substantially outnumber liberal/progressives in white working class America.

Part of the difficulty is weaknesses in standard ways of polling, which uses conventional framing (i.e. elite framing) to force people into yes / no answers, and then aggregates across relatively gross categories (white, or white working class) and then overemphasizes slightly differences in means across such categories (i.e. 30% versus 25%?). Different types of questions yield different types of results, yet only some of these get treated as truth.

When questions about moral issues are not framed as abstract statements of approval or disapproval for traditional “morality” in general but rather as questions about the more practical question of whether government should be made responsible for enforcing conservative morality, only 29% of white working class voters turn out to be conservative “true believers” who strongly agree with the idea. In fact, a significantly larger group of 43% strongly disagrees and holds that the government is actually “getting too involved” in the issue.

But even more significant, nearly a quarter of the respondents are somewhat ambivalent or open-minded on this issue. As the chart below makes dramatically clear, they represent the key swing group whose support can convert either side into a majority.

It’s easy to move unproblematically from the results of polls to interpretations about people, but there is always interpretation involved, framing always matters, and there is always simplification. We (social scientists, especially) prefer the idea that if we just choose the right tools than interpretation is unnecessary. But that’s simply not true. And if interpretation isn’t done explicitly and carefully, we end up just using our own biases and stereotypes.

The other issues concerns on what terrain you contest. But of course, sometimes financing campaigns is in tension with appealing to voters.

As can be seen, on the distinct subset of “populist” issues about corporate profits, power and the role of wall street a majority of white American workers—54%—strongly agree with a liberal/progressive view. In contrast, only 20% strongly agree with the conservative, pro-business perspective.

(All this reminds me of the controversy over the role of African-Americans in the approval of Prop 8. Classism remains a serious problem.)

Of course, getting this wrong stands in the way of changing things. It’s easy to believe that progress is stymied because a large swath of the population is inherently opposed to your goals. It lets you off the hook. To believe that people can change places a responsibility on activists to reach out, to do the hard work of organizing.

But it’s not true. The road ahead may be difficult. But it’s not impossible.

Citizens United and the Way Out

[Updated below]

A common refrain is that until the problem of money in politics is dealt with, we can’t achieve anything. Often, the focus is on Citizens United*, and the necessity of a constitutional amendment to overturn it. The difficulty here should be obvious – enacting a constitutional amendment is exceedingly difficult, it would require gaining support from plenty of red states in addition to the blue and purple ones, it would require a set of strategies different from those common in campaigns now (i.e. ad driven, because why would big money donors support it), etc. How could this be achieved in a system that is broken? Obviously, one needs a way to improve the situation that can operate within the existing system, or there is no way out. By focusing on a constitutional amendment (without offering a path to get there), we offer people two choices – fatalism, or magic thinking. Neither view is very useful.**

It strikes me the key is to 1) find strategies that rely less on big money, preferably by harnessing the energy of the large majorities of Americans who oppose Citizens United and are concerned about corruption in politics and 2) finding reachable, intermediate goals that could create a path to major change but wouldn’t require it in order to be achieved.

In terms of strategies, face to face interaction is more powerful than advertisements both in getting people to vote and in engaging them to act. This would require building a permanent organizing infrastructure (that is, one that is not created and dismantled around individual campaigns). It would mean relying on volunteers over paid staff. And it will require choosing frames that inspire excitement and support rather than those that poll well with independents. This sort of organizing can’t be limited to elections–when people mobilize to elect candidates and then demobilize when those candidates take office, the policy that results will be a disappointment, as corporate interests and conservatives will continue to fight. It has to include battles over policy and organizing in the workplace as well.

What about the intermediate steps? Well, first corporations can be pressured directly to disclose their spending, and shareholders can pressure corporations not to use their money to advance political causes. (On the latter, remember the recent efforts to pressure corporations to stop supporting ALEC). The rules governing corporations could be changed to require them to get shareholder support in order to engage in electioneering or lobbying. Public funding could be instituted at the state level (as long as they don’t include a trigger where candidates get more spending when they are being outspent the Supreme Court is unlikely to strike it down ,and it’s not clear that these triggers are necessary.) And as an organizing infrastructure is created, it can be used to support candidates who in turn could be pressured not to use media strategies that require large donors.

None of this would be easy, but all of it is easier than a constitutional amendment. Regardless, any approach has to operate within the system.

*I’m not convinced that Citizens United is the problem. The system was fairly broken before that decision. There’s little doubt that in the wake of the decision the amounts of campaign cash skyrocketed. But simply returning to the pre-Citizens United rules would be no solution, and neither would placing spending limits on corporations alone.

**I’m leaving aside the question of disclosure, because I fail to see how 1) it’s possible using existing strategies or 2) why it would matter much. I knew a number of people who worked in the business campaign finance sector in the late 90s. Back then, any conversation about campaign finance ended with their suggestion that the solution was full disclosure. I don’t think it was because they wanted to limit the power of business.

[Update]

David Dayen has a really good take on how the decision to go forward with a recall in Wisconsin narrowed the possibilities there that’s well worth checking out. A taste:

The populist movement that arose from the uprising could have used every dollar given to a politician or an outside campaign spending group and used it in community-based organizing. We could have seen well-funded nonviolent actions. We could have seen education campaigns, going door to door with a message rather than an ask to support Tom Barrett or whoever else. We could have seen economic boycotts on Walker-supporting businesses. We could have seen more organizing into broad coalitions around the idea of repealing the rights-stripping collective bargaining law. We could have seen an insurgent movement, one that captured the energy of the uprising rather than re-channeled it.

The Death Penalty and the Perils of Progressive Fatalism

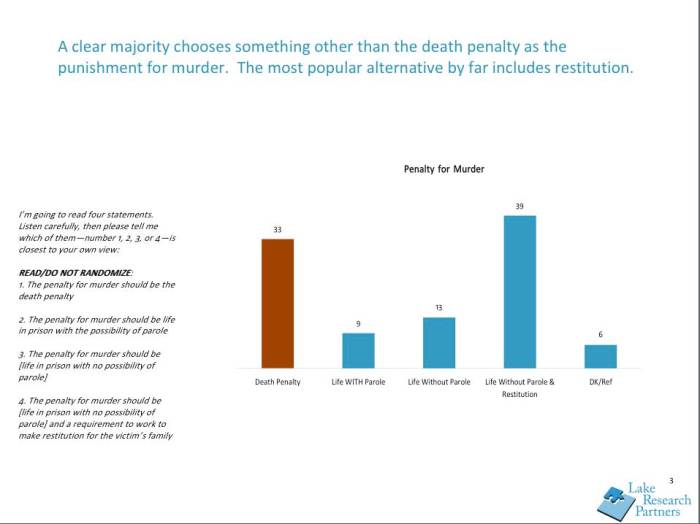

Today, Up With Chris Hayes featured a good discussion of wrongful convictions and the death penalty. But Chris repeated a misleading claim about public opinion on the death penalty that highlights a larger problem. The claim was that Americans overwhelmingly support the death penalty, and therefore efforts to repeal the death penalty face a serious challenge in terms of changing people’s minds. Chris pointed to a poll showing that a solid majority of Americans said the death penalty was morally justified. More typically, people point to polls that ask simply if people support or oppose the death penalty.

Intuitively, this makes sense. The problem is that it’s a false choice. When polls offer people alternatives to the death penalty, those numbers shift considerably. Gallup has shown this for some time. When offered the choice of the death penalty versus life without parole, public opinion is evenly split. The abolitionist Death Penalty Information Center offers an even more nuanced look.

Note, this poll doesn’t offer people new information, it simply gives them additional choices. What happens when people do hear new information? The numbers shift even more.

What does this mean? It means that many of those people who are allegedly supportive of the death penalty would chose another penalty if given the choice. It means that ‘support’ is soft. Hardly the stuff of fatalism.

I know why someone who supports the death penalty might prefer the first set of questions over the second. But why would an opponent? And Chris is not unusual here. Why do death penalty opponents so often fail to offer the full picture? I don’t know the answer. I suspect a lot of progressives, after years of conservative dominance (which is not the same as majority support for conservative opinions) have adopted an identity of being on defense, of being outnumbered, and just see the world through that lens. But doing so is both distorting and poses a barrier for those who seek progressive change.

* I’m leaving aside three important issues. First, public opinion does not generally drive policy. Second, results of polling is not the same as strongly and sincerely held opinions. Three, we know that polling responses are partly a product of elite discourse. Right now, both parties are pro-death penalty, and as a result, so is the media. If one party were to offer a different view, it would change media coverage and likely move polls as well.